Collecting Seeds, Saving Ecosystems: Partnerships for California’s Native Plant Restoration

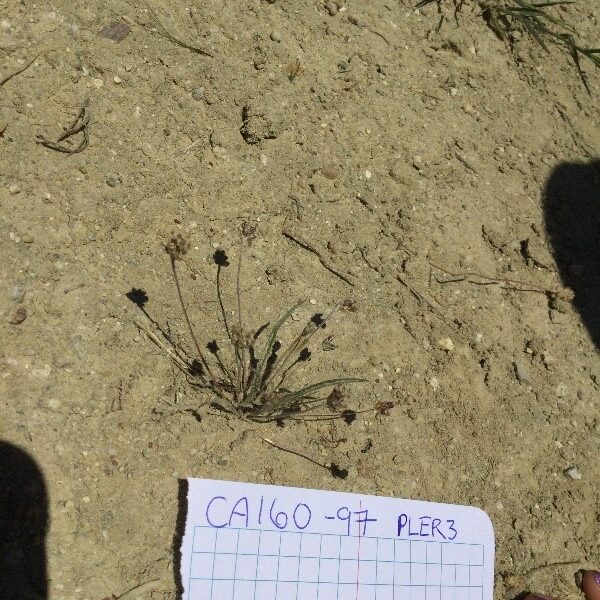

It was mid-April when the first heat wave hit southern California, and the Central Valley looked mighty crispy. With the heat, we sensed that some plants might be going to seed much earlier than expected. Sure enough, scouting around the oil fields near Taft, CA, we discovered a large population of one of our target species, a tiny powerhouse called desert plantain (Plantago ovata). It was ready to collect! We commenced our first seed collection of the season, crawling across the hot sand, gathering seed from hundreds of plants just a few inches tall.

Seeds of Hope

Not more than an hour later, the wind picked up, and we started smelling smoke. A brush fire had ignited a couple of miles away and was blowing directly towards us. We moved out of the path of the smoke and continued working for another hour, throwing seed in our bags as fast as we could. We booked it out of there as we saw flames approaching a nearby ridge.

We decided that although we didn’t reach our target seed count of 80,000 seeds for the collection, we had a very good excuse. We later learned that the fire had burned the exact area we collected from. Depending on how the area recovers, those seeds might come in handy sooner than we expected. If the population didn’t survive that fire, now we have a backup.

Conservation and Partnerships

Unlike the rest of the rare plant team focused on researching and collecting rare and endangered seeds, my field season was dedicated to sustainably collecting more than one million seeds from various common native plants for a national program called Seeds of Success (SOS). Led by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the program funds the collection, conservation, and production of native seed to restore our public lands. The program achieves this through partnerships with various organizations, like Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, that perform different functions. Our role at the Garden represents the first step in the process, which is scouting and sustainably collecting seeds from large populations of common native plants that are valuable for the restoration of degraded areas, such as oil fields in the Central Valley. Even those areas still contain glimmers of a once-flourishing ecosystem. From a few small parcels, we were able to scout large populations of desert plantain (Plantago ovata), bladderpod (Cleomella arborea), pine bluegrass (Poa secunda), and burrobrush (Ambrosia salsola), plus a bonus sighting of the rare San Joaquin Le Conte’s thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei).

What Do We Do With All These Seeds?

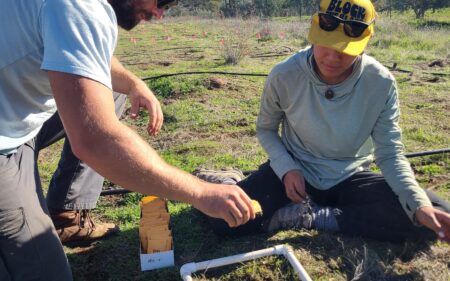

To preserve the genetic diversity of locally adapted ecotypes, the populations we survey and collect from must be of wild origin. This means humans did not plant them in the last 500 years. Planning, scouting, collecting, and shipping our seeds takes months. We also take clippings of the specimens to document our collections in our Clifton Smith Herbarium and the Smithsonian Institute. Before a plant (or pieces of plants for large things like trees) is accessioned into an herbarium, it must be pressed, dried, mounted, and documented. Herbarium specimens provide not only a record of what we collected when and where but also create opportunities for other botanists interested in studying the timing of life cycle events, biogeography, and even genetics.

Because we collected thousands of seeds, we shipped them to an industrial seed-cleaning facility in Bend, Oregon, for processing. Depending on the species that was collected and the size of the collection, the seeds can serve multiple purposes. Some species, like those in the genus Dudleya, are not well represented in SOS collections. These collections are sent to the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation, our nation’s primary seed bank, in Fort Collins, CO, for long-term conservation storage. Large collections of restoration-worthy plants are returned to the BLM, which partners with growers to scale up the operation, planting the wild-collected seed as agricultural crops to be harvested. This method of “seed bulking” is essential to facilitating large-scale restoration projects because it reduces the ecosystem impacts of harvesting seeds, which are imperative for plant population persistence and often provide a vital food source to many critters. We could never harvest enough wild seed to restore America’s public lands, but by farming wild-collected seeds, we can amplify our field efforts and produce sufficient seed for large-scale restoration.

We Cover a Lot of Ground

This year, the Garden’s SOS team focused on making SOS collections in the BLM’s Bakersfield Field Office, which covers a large and diverse geographic area. In fact, the Bakersfield Field Office covers more area than any other office in central California – more than 720,000 acres! That’s a lot of ground to cover. Overall, our team scouted 70 native plant populations for SOS across the central coast, Sierra Nevada Foothills, and Central Valley, providing critical survey data for future collectors. We made 20 seed collections from 15 unique taxa, 11 of which had never previously been collected in the Bakersfield Field Office and 12 from never-before-collected BLM parcels. By emphasizing unique taxa and field sites, our 2024 collections diversified the species and geographic areas represented in the SOS collection, enhancing opportunities for future restoration.

In 2025, our fieldwork focus will be seed collecting from rare native plants, an equally noble mission at a totally different scale. This means the days of collecting seed into grocery bags are over for now. Instead, we’ll be using coin envelopes for rare plants! However, this will give me a break from the absurdity of storing more than one million seeds at my desk. Preserving rare seed is a more delicate process to ensure every seed counts!

Seeds of Change: Conservation Through Diversity

To learn more about seeds and the Garden’s efforts to understand, protect, restore, and grow native plants (and seeds), join us for our 12th Annual Conservation Symposium. This year’s theme, “Seeds of Change: Conservation Through Diversity,” will explore the fascinating diversity of seeds, emphasizing their importance as living resources crucial to our planet’s ecological health.

Donate

Donate