Adding to California’s Native Lawn Lineup

Non-native turfgrass lawns may be widely planted in southern California, but they simply do not belong here. To many people these ubiquitous green carpets of grass seem inoffensive, even desirable. But after years of droughts, fires, and mudslides, many Californians are beginning to understand that it’s past time for us to rethink their presence here. There are plenty of good reasons for that.

Traditional lawns are an outsized drain on our resources. They do not contribute food or habitat for humans or other animals, stabilize the soil very well, and the pesticides and the over-application of fertilizers needed to keep them uniformly green and lush cause a multitude of problems. Not to mention their excessive water needs. Typical species of lawn grass require significantly more water than their native counterparts. Using Santa Barbara County’s Waterwise calculator, in a typical Santa Barbara yard, a non-native turfgrass lawn needs an estimated 48,000 gallons of water per year. Compare that with a landscape of native plants, which would need an estimated 14,000 gallons of water per year.

There are a great many unnecessary lawns carpeting the landscape in Southern California, and many of these areas should be replaced with native shrubs and perennials. However, as a lover of picnics and the owner of a fetch-obsessed dog, I can’t quite bring myself to condemn all lawns. A functional lawn is still important to many of us. Those of us with children or pets and those of us who love to play sports appreciate what a good lawn can be at its finest. Fortunately, there are other options besides the typical non-native turfgrass species and a yard full of chaparral shrub species (which are beautiful but admittedly difficult to picnic on). California native grass lawns might be the perfect solution.

A Case for Native Grass Lawns

It may be tempting to imagine that a grass is a grass and that there are no significant differences between species. However, native grasses actually provide many benefits when compared with traditional non-native turfgrasses. Typical turfgrass species such as Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), which originates in Europe despite its common name, and ryegrass (Lolium sp.) were selected for their appearances and their tolerance to foot traffic. However, they are delicate plants that need lots of hands-on cultivation to stay green.

The most important difference between these non-native turfgrasses and native grasses can be found underground. Native perennial grasses have deep roots, and these often stretch several feet deep into the soil. Contrast this with the shallow root systems of non-native grasses, which only spread a few inches below the surface. The deep roots of native plants are excellent at preventing erosion, slowing down runoff, and filtering water. Furthermore, native grasses are very resilient. The aboveground vegetation can die off due to drought or fire, while the roots stay alive underground. This resilience of native grasses means they are great at capturing carbon and storing it long-term. It’s even been shown that grasslands can be more effective for carbon sequestration than forests due to their ability to survive after wildfires and droughts.

With all these benefits, it’s clear why home gardeners might want to incorporate native grasses into their home lawn and landscape and perhaps even recreate a native grassland in miniature. Unfortunately, this is easier said than done at present.

Advancing Horticulture Research

There are some hurdles to homeowners unveiling a lawn of native grasses, namely selection. There are relatively few native species of grasses that are currently available for use as turfgrass. Clustered field sedge (Carex praegracilis), seashore bent grass (Agrostis pallens), blue grama grass (Bouteloua gracilis), are the three major ones, but they are not universally suited to the many microhabitats that can be found across the state. Additionally, lawns perform best when they are grown from a blend of several species of grasses, and the more species we have available, the better. To begin to chip away at this problem, we applied for a research grant through the Saratoga Horticultural Research Endowment to fund the collection and propagation of an alternative species of California native grass, new to cultivation Hoover’s bentgrass (Agrostis hooveri).

Hoover’s Bentgrass (Agrostis hooveri), a Good Native Lawn Candidate? We’ll Soon Know.

Adapted to dry soils in oak woodlands, Hoover’s bentgrass is a native species of grass known only from Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo Counties. Due to invasive species and development destroying its habitat, it is a very rare species in the wild. It’s also a close relative of one of the other lawn alternatives that are more widely available, seashore bentgrass.

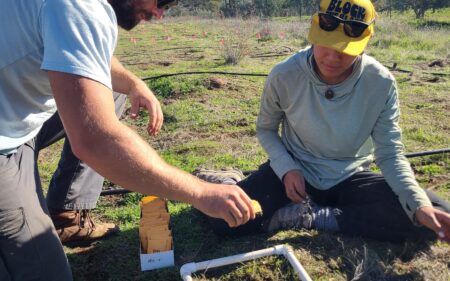

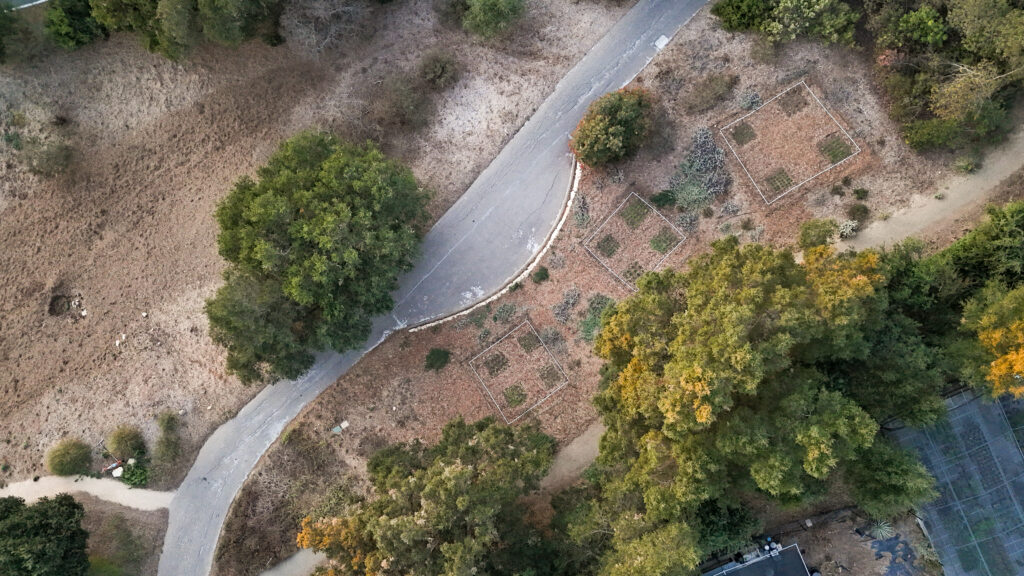

After successfully cultivating a crop of Hoover’s bentgrass in the nursery, we were ready plant them into the ground. Our goal is to learn more about how Hoover’s bentgrass handles common home garden conditions like deep shade, foot traffic, and summer watering. To do this, we planted miniature lawn plots at the Garden to recreate each of these conditions. We also planted a control plot.

We are testing how Hoover’s bentgrass performs alongside other native grass species. The test includes plots of three other grasses, seashore bentgrass (Agrostis pallens) the common lawn alternative, western fescue (Festuca occidentalis), and purple needlegrass (Stipa pulchra). The grasses in each plot are trimmed once a week to simulate regular mowing. One plot is subjected to foot traffic, and one plot is being grown in shade. For each plot, we measure the percent cover once a week until the end of the growing season to see how these mini lawns fill in.

Ultimately, we hope to learn more about which species of California’s native grasses will do best in this very specific type of cultivation. Then, work towards getting more native plants in yards across the region.

We want to recognize Saratoga Horticultural Research Endowment for its generous support of this research. To learn more about the power of native plants and the Garden’s commitment to advancing horticulture, visit the link below.

Donate

Donate