Carrizo Plain in Bloom: A Glimpse at the Endangered California Jewelflower

Spring is a special time at Carrizo Plain National Monument. A good rain year can bring out spectacular displays of native plants blooming in various shades of yellow, orange, and purple across the Monument’s wide plains and rolling hills. Each plant species, with its specific color, shape, and size, is an important part of this colorful symphony, adding complexity to the landscapes that wildflower lovers chase each spring.

One of the rarest members of these blooms is the California jewelflower (Caulanthus californicus), a small plant in the mustard family (Brassicaceae) that is state and federally endangered. Though small, it is a striking plant, producing a stalk covered in delicate cup-shaped white flowers culminating in a deep maroon cluster of buds. Endemic to central California—meaning it naturally exists nowhere else in the world—the historical range of jewelflower has been dramatically decreased by land development in the Central Valley. The species is now only known to persist in the San Joaquin Valley and the adjacent slopes of the Central Coast Ranges. The plants in Carrizo represent healthy populations of this endangered species, giving us an opportunity to learn more about it and, ultimately, protect it.

In 2022, the ecology team at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden set out to discover what insects pollinate California jewelflower, an important piece of information as we attempt to maintain healthy populations at Carrizo. If the species depends on a few specialized pollinators, for example, we can assume that declines in those insects would further threaten jewelflower. As we learned more about the species, it became clear that it could benefit from closer monitoring. Were these jewelflower populations stable, decreasing, or growing? Do weather, pollinators, or both determine these trajectories? And so, the jewelflower demography project came to be.

Demography is the study of populations, which are made up of individuals. The lives of annual plants like jewelflower are fairly simple: they live underground as seeds until environmental cues tell them to wake up and germinate. If they survive until flowering, they hope to get pollinated and then produce seeds that go back into the soil until the next favorable year. To understand whether a population is healthy, we need to know how individuals are germinating, growing, flowering, and setting seed. To do that, we need to follow the lives of individual jewelflower plants very closely.

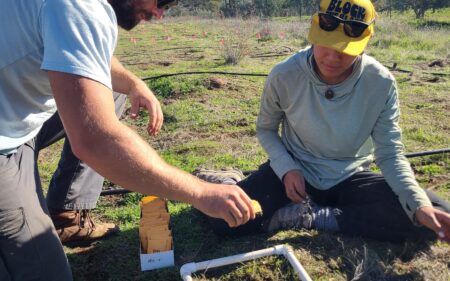

During the spring of 2023 and 2024, the Garden’s rare plant team visited Carrizo every two weeks to check on 778 individual jewelflower plants. Armed with clicker counters and a small measuring tape, we crouched down next to hundreds of marked individuals, careful not to step on any surrounding jewelflower, and counted how many flowers and fruits they had, measured their width and height, and took extensive notes on whether anything ate them while we weren’t watching. Over the course of the season, we got to know the individuals at Carrizo well, noticing where they grew tall and spindly, where they were completely munched, and where they seemed happiest. The more we looked, the more questions came up.

For one, we saw many jewelflower plants that had lost their stems and leaves to a mystery herbivore, so we set out camera traps to discover what was causing so much damage. We suspected that a charismatic rodent might be involved, as jewelflower often grows on and around its burrows. As it turns out, botanists are not the only animals attracted to the California jewelflower. We discovered the (also federally endangered) Giant Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys ingens) is the primary herbivore of these plants at Carrizo. Our camera captured dozens of videos of the adorable rodents taking out whole stems, leaves, and flowers. As the kangaroo rats themselves are eaten by the federally endangered San Joaquin Kit Fox, our observation connects jewelflower to a whole food web of endangered animals, exemplifying the importance of rare little plants in the larger ecosystem.

With two years of data in hand, some patterns are starting to emerge. For example, we see some differences between the three populations we are studying, with one consistently showing higher fruiting than the other two. Our observations suggest this may be due to the amount of floral herbivory at the different sites, which we will continue to monitor. However, following plants for only two years cannot answer our main question: Are these populations stable, decreasing, or growing? To do that, we will need more years of springtime visits, following hundreds of future jewelflower as they journey from seed to seed. Along the way, we hope to continue discovering new details about how this plant interacts with the other jewels of Carrizo Plain, from pollinating insects to adorable endangered mammals and beyond.

To learn more about how the Garden is working to protect California’s native plants, especially our most rare and endangered plants like the California jewelflower, follow the link below.

Donate

Donate