A Climate-Forward Planting Experiment Teaches Right Plant to Right Place

Here’s a scary fact: by the year 2080, the climate in Santa Barbara is projected to approach that of present-day Ensenada, Mexico. Already, temperatures are rising and drought is increasingly frequent. What’s a sustainable gardener to do? In my hot, dry, south-facing Santa Barbara yard, which my husband and I rarely watered (and where I no longer reside), we found success with native plants from more arid portions of southern California. That was my inspiration for the climate-forward portion of the plant palette at the Elings Park Transformation Garden.

In this experiment, we have been testing out seven species from farther south, including Shaw’s agave (Agave shawii), Golden-spined cereus (Bergerocactus emoryi), California boxthorn (Lycium californicum), and desert mallow (Sphaeralcea ambigua). Most of these plants come from a plant community called maritime cactus scrub, an assemblage found only near the coast, that is adapted to both a hot and dry environment, but also coastal fog. There is little of this community left due to land development and other human disturbances, and it has few opportunities for northward migration. Some of its species are quite rare – Shaw’s agave, for instance, has been reduced to just two naturally occurring populations, with just one individual comprising one of those. Many of the plants are also naturally well-defended – a benefit at Elings Park, where there is an abundance of rodent herbivores.

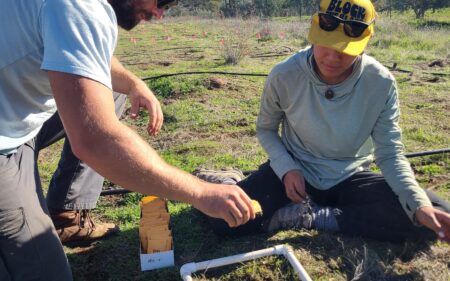

We planted these seven climate-forward species at Elings Park along with 22 common central coastal plants, including sages (Salvia spp.), coast sunflower (Encelia californica), and California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum). We have aimed to answer the following questions: Do these southern natives survive and grow as well as, or even better than, the locally collected natives? And crucially, do they support as much insect and bird life? A year and nine months after planting, we have a good idea of the answer to at least the first question.

On the whole, survival has not been significantly different between the more arid-adapted natives and central coast species at Elings Park. Average biomass, however (which we estimate via a calculation using two measurements of width and the height of the plant), is significantly higher for the central coast plants. That, in turn, depends on which type of weed-control plots the plants are located in: those that utilize sheet mulching, or layers of cardboard and wood chips, or those that were covered with black plastic for months prior to planting. Mulching has been great for the growth of both central coast and southern plants, with biomass in the sheet mulched plots about double that of the tarped plots.

Beyond those general results, however, there is more to the story, with some species performing better than others. Some predominantly southern but also inland species, like desert mallow and bladderpod (Cleomella arborea, which is found mostly to the south but also inland), have fared fantastically. They grew quickly, bloom much of the year, and support a pethora of pollinators. They spread readily and would make a beautiful addition to any garden, provided you don’t mind the slightly skunky smell of the bladderpod. The somewhat sulfurous odor has been called “whitch’s fart” in some Spanish-speaking regions – but can you blame it for this natural defense mechanism against those who would eat it?

I wasn’t sure how desert indigobush (Amorpha fruticosa) would fare, as it likes somewhat moist soils, but I hoped that the heavy clay at Elings would give it what it needs. I chose this native to Los Angeles County, south is because it is host to a variety of butterfly and moth larvae (caterpillars), including that of the southern dogface butterfly, which is California’s state butterfly. This winter deciduous shrub has grown quickly, and its deep reddish purple flowers, which house a spray of yellow stamen, are just glorious.

Two of the maritime cactus scrub species, California boxthorn and cliff spurge (Euphorbia misera), are holding their own. While defended with small spines and a somewhat toxic sap, respectively, they are also a bit delicate, and the branches are easily broken. This doesn’t always pair well with the feet of the many human helpers needed to keep the site’s weeds in check. Relatively low-growing species, they can also be overshadowed by taller shrubs.

overshadowed by its more aggressive neighbors.

This brings me to the golden-spined cereus, the only member of the cactus family that I chose for the site, because it is one of the nicest cacti I know. It grows like fingers that glow beautifully with delicate spines and, over time, forms dense clumps in maritime regions. This has unfortunately been one of the most poorly performing species, as it is both vulnerable to breakage when young and does not like being crowded by the many weeds at the Elings Park site. Maybe it’s for the best, as even the gentlest cactus still doesn’t feel good when accidentally encountered.

on Todos Santos Island in Baja California, Mexico.

The spectacular Shaw’s agave doesn’t like being smothered by weeds any more than the next plant, and its spiky edges make it a bit painful to liberate it from these insidious invaders – but it is a bit more obvious than some of the more delicate members of the maritime cactus scrub, and is thus more resistant to trampling. It seems to be surviving well at Elings Park. While it is somewhat slow-growing, it will eventually form big, beautiful clumps. With the addition of a few more genetic types from its remnant range, Elings Park could also become an important conservation collection for this species.

impressive flowering stalks.

Nature is beautifully complex, so it stands to reason that the answer to the question we posed (do the more arid species perform as well as or better than local central coastal species?) is not so simple. Two important factors noted here have been the extreme weediness of the Elings Park site and the heavy human traffic associated with its restoration. In my Santa Barbara yard, a fresh layer of decomposed granite covered the weed seed bank and allowed us to create a clean, open environment mimicking that of the desert-climate species, which are naturally more spread out. And, of course, we knew well which plants to avoid; our hundreds of volunteers come with a wide range of experience.

Then there is the fact that, while the climate in Santa Barbara is projected to be more like Baja California, Mexico, in 2080, we’re not there yet. My yard’s location, over three miles from the coast, made it significantly hotter and drier than Elings Park, which is less than a mile from shore and experiences more frequent coastal fog. So, while many plants and animals will need our help surviving and thriving in a changing climate, it will be a gradual and nuanced journey, not a one-and-done.

All of this speaks to how important it is to get the right plant to the right place, both in conservation and in our own home gardening. Adaptations to local soil, temperature, moisture levels, and more are the reason we have so many native plant species in California, and so many different animals that love them. These adaptations, and the sustainability that comes with it (fewer water and fertilizers needed, more pollinators and other critters supported) are what make gardening with natives so wonderful – and honestly, also a bit frustrating at times, when we don’t get the site quite right and we have to try again. But who wouldn’t say that a flourishing patch of Matilija poppy (Romneya coulteri), woolly blue curls (Trichostema lanatum), or flannelbush (Fremontodendron spp.) is worth it? Especially when, along the way, we learned a little something about nature.

Donate

Donate