Seven Questions with Senior Rare Plant Conservation Scientist Heather Schneider, Ph.D.

Few people can call the natural world their office. However, Heather Schneider, Ph.D., the senior rare plant conservation scientist at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, isn’t one of those people! Her full-time job is to understand, protect, and restore California’s rare native plants – and she’s been growing her team and the Garden’s collection of rare native plant seeds for more than eight years!

Following the craze of this past season’s “superboom” with its captivating swaths of yellow, orange, and purple wildflowers blanketing our hillsides, it’s easy to see why California’s native plants are so special and worthy of protection. Yet, it isn’t the bright colors or the fragrant blooms that drive Heather’s work. It’s the vital role native plants have in supporting a healthy, thriving ecosystem. The kind you and I need to survive!

Join us in this episode of “Seven Questions” as we walk with Heather to learn more about her and her life’s work as a rare plant conservationist.

Let’s start at the beginning. For those who may be unfamiliar, what is your role as a garden senior rare plant conservation scientist and what does a typical day look like for you?

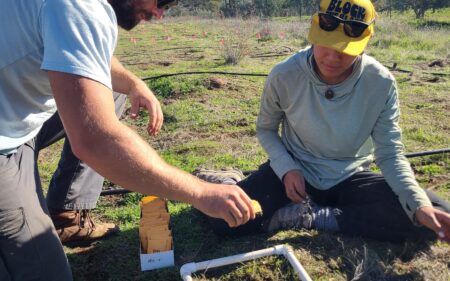

[Heather] So, in a nutshell, I oversee the Garden’s rare plant conservation. It’s a big job, but I have a wonderful team of people helping me here at the Garden and one of my favorite things about my job is that I don’t really have a typical day. In the spring and summer, I’m often in the field somewhere in California, camping and hiking, looking for rare plants, and doing research. In the offseason, I’m here in the Pritzlaff Conservation Center analyzing data, writing reports, and seeking funding to continue our work.

Can you tell us why some plants are rare?

[Heather] There are a lot of reasons that plants can be rare, but we sort them into two buckets. One is intrinsic factors. That means that there’s something about the plant itself that makes it rare. It could be that it’s tied to a specific soil type so they really can only grow in a few places. Then the other bucket is extrinsic factors. These are things outside of the plant that create pressure, or that reduce numbers or habitat for that plant. So that’d be things like habitat loss to development or climate change. Often plants experience a little bit of both.

You recently worked on the delisting of the Santa Cruz Island Dudleya. What does it mean to delist a plant?

[Heather] Plants are put on the federal endangered species list when they are at high risk of extinction, and in the case of Santa Cruz Island Dudleya, in the 90s when it was listed, they were under great threat of feral pigs that had been introduced to the island. In the early 2000s those pigs were removed and the plants had a chance to naturally recover. A lot of conservation and research went into understanding how those plants are doing. Taking them off the list means that we feel comfortable that they’re on a positive trajectory for the future and that they don’t need long term protections under the ESA any longer.

That’s an amazing success story. If recovery is attainable, does that suggest that there’s still hope for the environment?

[Heather] There is! I feel like it can be really overwhelming with everything going on in the world right now. It can be hard to stay positive, but I think focusing on success stories like this is really important. And the idea of thinking globally and acting locally, I think can empower us as individuals and organizations to think about challenges that we can bite off and tackle. And that’s what we’re doing here at the Garden every day. These kinds of successes are really exciting to celebrate.

You also work in the seed bank. The Garden Seed Bank isn’t something that every visitor gets to see. Can you tell us where it is and how many seeds are in your collection?

[Heather] We have a nationally accredited Conservation Seed bank here. It’s tucked away safely in the PCC behind me and we have a collection of more than 3,000,000 seeds representing rare plants in California. And that is sort of acting as an insurance policy against extinction for more than 330 different kinds of rare plants.

You’ve said that collaboration is the heartbeat of conservation. Can you elaborate on this and some of the partnerships that’s been essential to your work?

[Heather] Conservation is a big, multifaceted field. We need to answer questions from the level of genes up to ecosystems. And thankfully, here at the Garden we have a diverse team of scientists who are equipped to answer all of those questions but we also have to collaborate with people outside of the Garden who have different expertise and experience that can help us solve these big problems. One of my favorite projects that I led recently was focused on 14 listed plants across 7 of the 8 Channel Islands. We worked with eight different partner institutions to make more than 540 rare plant observations, bring in more than 100 conservation seed collections and answer a lot of different research questions that are pushing things forward for conservation on the islands. One of those plants was the Santa Cruz Island Dudleya. Our work directly impacted the delisting that just happened this month.

Since everyone can’t possibly join you in the field, what’s one thing that they can do at home to help protect rare plants?

[Heather] I really wish that everybody could get in the field with us. It’s such a magical and awe-inspiring experience to get out in nature. But if you can’t do that, I would really encourage people to engage with the natural world in whatever way is most intuitive for you. For me that means going on a hike on our local trails. For you, it might be going to the beach or a park, or just sitting in your own garden and writing poetry or making art based on what inspires you. I think that the most important thing is to start cultivating that personal relationship with nature. And I hope that once you do that, you might not be able to help but work toward conservation in your own way.

According to NatureServe, 34% of plant species are at risk of going extinct and it takes years to bring a plant back from the brink. So the time to act is now! The Garden and Heather’s team is committed to doing our part to ensure no native plant goes extinct on our watch. Will you join us in this work?

Donate

Donate