Saving the California Jewelflower: A Journey from Seed to Survival

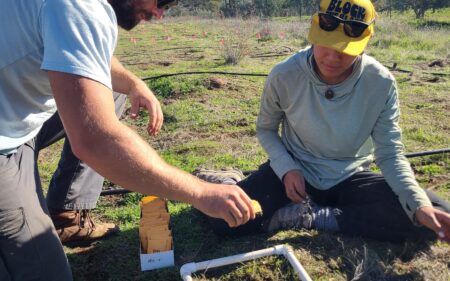

For several years, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden has been working to deepen our understanding of the state and federally endangered California jewelflower (Caulanthus californicus). This beautiful annual plant is facing habitat loss due to destruction associated with agriculture, oil fields, and urbanization. Since 2017, the Garden’s rare plant team has been following populations of California jewelflower at Carrizo Plain National Monument, conducting periodic surveys, and collecting seed for safekeeping in our Conservation Seed Bank.

Over the years, we’ve been able to track how the Carrizo Plain’s population of California jewelflower is doing. We’ve also been able to uncover clues about the vital role this rare plant has in maintaining ecosystem balance on the Plain. For example, our ecology team has been investigating the plant’s complex pollinator interactions, while our rare plant team has been closely monitoring its demographic patterns, how the population changes over time in terms of numbers of plants, timing of flowering, and effects of herbivory and plant size, in the wild.

Earlier in 2024, the Garden’s nursery became part of this critical work. Our goal? Grow the jewelflower ex-situ, or out of its natural setting, so we can learn more about and produce as many seeds as possible (a strategy known as “seed bulking”). By increasing our supply of California jewelflower seed, we can better ensure its survival. However, to achieve this, we needed to bring jewelflower seeds to life, care for them, hand pollinate them, and then collect as many seeds as possible to aid in future restoration efforts.

Getting Started: Germination

To get started, we need to access some of the wild seed we had collected on previous trips to Carrizo Plain National Monument. In December 2023, we removed 124 wild-collected seeds from our Conservation Seed Bank to start our seed bulking project. The seeds we used represented two different populations at Carrizo. Armed with guidance from a previous germination study, we got to work, hoping to achieve high germination rates from a notoriously difficult species.

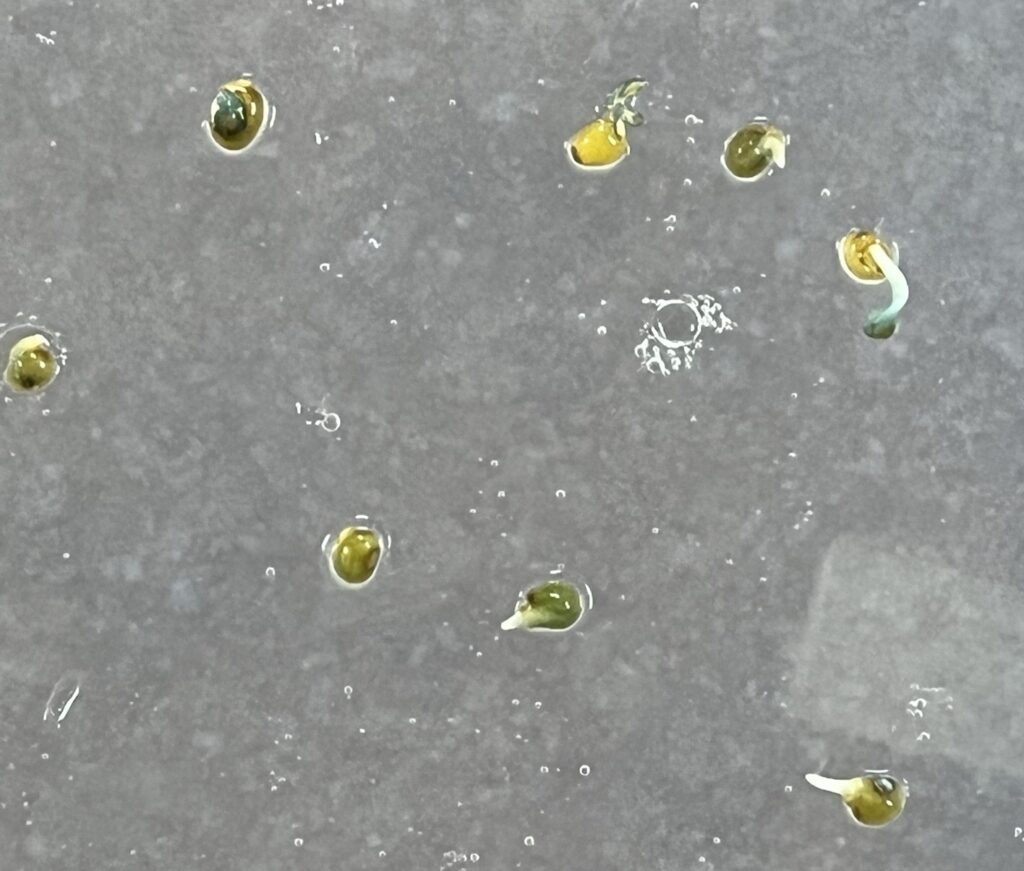

The first step felt a bit like performing surgery. Under a microscope, I carefully removed a small section of the seed coat with a scalpel, exposing the embryo inside. This made the seed more receptive to the next step: a soak in Gibberellic acid (GA3), a natural plant hormone that helps break seed dormancy and promotes germination.

After their GA3 bath, the seeds were placed in the refrigerator for a cold stratification treatment (i.e., temporary exposure to cold temperatures) to mimic a winter chill. The result? An amazing 99% germination rate, far exceeding any expectations we had!

Up Next: Transplants

With germination now in the rearview, it was time to move the tiny seedlings from Petri dishes into individual cells of a plug tray, a tool used in horticulture to support the start seedlings. Even with the right tools, this is always a nerve-wracking process. Using tweezers, we gingerly picked up each seedling, ensuring we didn’t squeeze and damage the fragile roots or bury the cotyledons, the germinating seed’s first leaves, beneath the soil. You can imagine what a relief it was to find that the vast majority of the seedlings survived the transplanting process.

Once in the soil, the plants grew rapidly, and after a few weeks, they were ready to move into their final homes. The last stop for our new jewelflower plants was much larger pots, which give their roots room to breathe. This is also the point at which we separated plants from the two different populations, ensuring that they would not unintentionally cross-pollinate in a way that would not have happened in nature.

Busy Bees: Hand Pollinations

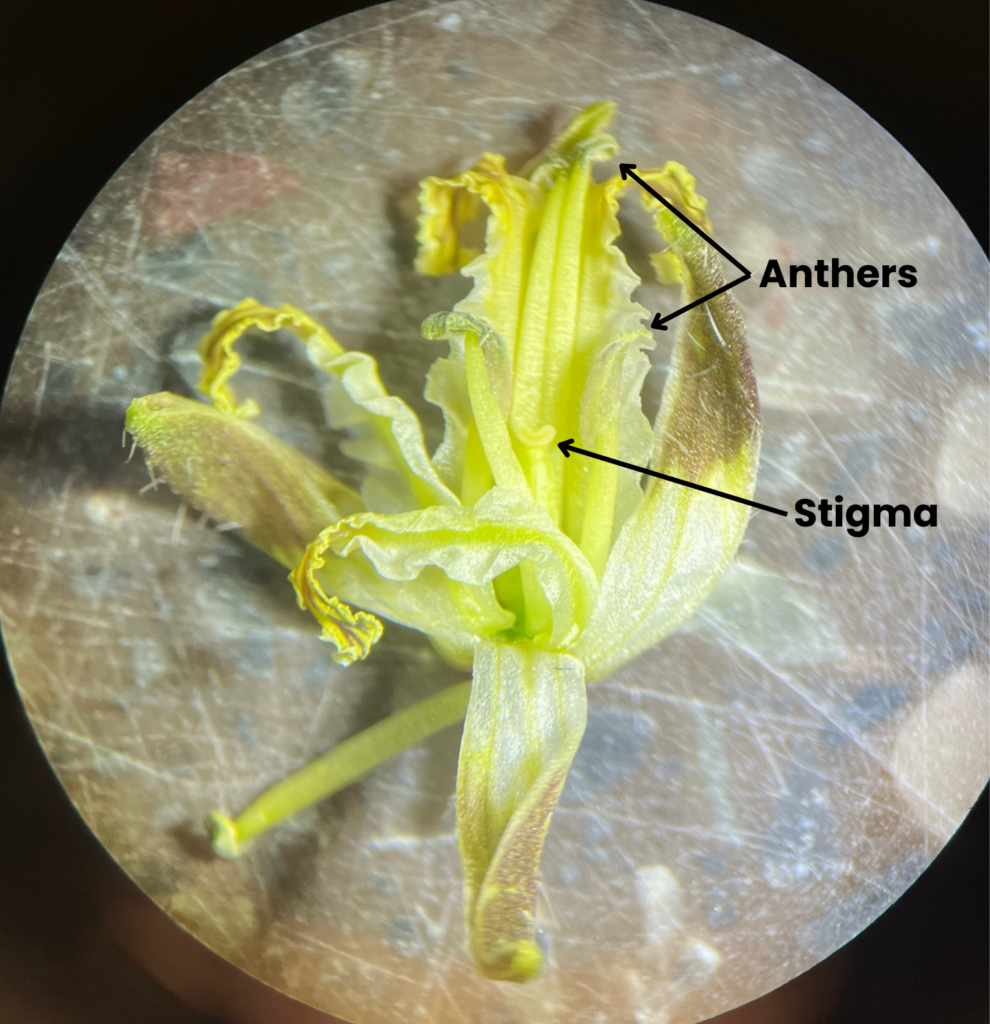

About a month later, the jewelflowers began to bloom, revealing long, slender flowering stems adorned with pendant cream-colored flowers, culminating in sterile flowers with deep maroon sterile flowers at the tip of the flowering stems. With this flowering came our next major task: pollination.

In the wild, bees and other pollinating friends would take care of this, but in the nursery, it was up to us. Using a fine-tipped paintbrush, I carefully transferred pollen from one flower to the stigma of another plant from the same population. This cross-pollination is essential for promoting genetic diversity, which also increases seed quantity and viability. It was also no easy task. California jewelflower blooms are complicated, and cross-pollination means delicately peeling back petals to move pollen from one flower to the next, all the while trying to prevent damage that would decrease the potential for fruit and seed development. For several weeks, my days were filled with pollination, moving from plant to plant, with a paintbrush in hand, just like a busy bee.

The Fruits of Our Labor

Thankfully, our hand-pollination efforts paid off. Over the course of two months, hundreds of fruits developed, each one containing dozens of precious seeds. Luckily, these seeds naturally announced when they were ready to be collected. Fruits would turn from a vibrant green to papery brown, and the fruits began to split at the seam. Dry brown fruits were snipped at the base and placed in a paper envelope. By early May, the final collection was made, marking the end of this special plant growing in the Garden’s Nursery.

Following the harvest, our nursery-produced seeds were moved into the lab to be cleaned and counted. A few sieves and a seed blower made quick work of the fruits, revealing our final product. What had started as 124 seeds and 110 plants had now become a collection of more than 200,000 seeds from two separate populations (kept separate, of course). These seeds added an important boost to the Garden’s conservation seed collections of California jewelflower and can be used for future restoration and research. For now, the seeds rest safely in the Garden’s Conservation Seed Bank, ready to be returned to the wild and share their beauty when the time comes.

Join the Native Plant Movement

You can help the Garden safeguard California’s native plants, including rare and endangered plants like the California jewelflower. There are many ways you can get involved!

First, join us in our goal to ensure biodiversity thrives by transforming the places where you live, work, and play with native plants. To get started, check out our growing library of resources to help you grow at home, and sign up for one of our many classes to refine your gardening skills. You can also work directly with our staff, supporting one of our various programs as a Garden volunteer. From working with our rare plant team cleaning seeds and getting your hands dirty with our gardeners to welcoming guests as a Garden host or lending your talents to the cause, you can help us make a lasting impact – from your backyard to the backcountry.

Are you ready to get started?

Donate

Donate