The Journey to Save Rare Plants: From Endangerment to Recovery Success

Update: As of November 2023, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has declared the Santa Cruz Island Dudleya (Dudleya nesiotica) and the Island Bedstraw (Galium buxifolium) as recovered and removed them from the Endangered Species list. You can hear more from Dr. Schneider in her interview with NPR.

As the first botanic garden to focus exclusively on native plants, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden has always been more than a destination. With more than 20 scientists on staff, a genetics lab, a seed bank, a tissue bank, an herbarium, and more than 50 active conservation projects, the Garden is taking action to ensure the survival of every native plant in our region. Why? Because native plants are the foundation for all life on Earth – including our own.

When biodiversity thrives, so can we.

Driven by this truth, we’re excited to introduce you to Heather Schneider, Ph.D., our senior rare plant conservation scientist here at the Garden. Together with her staff, Heather is leading our efforts to ensure no native plant goes extinct on the central coast. Recently, she and her team were at the helm of a crucial conservation effort that resulted in the “proposed delisting” of the Santa Cruz Island Dudleya from the endangered species list, a rare plant endemic to the Channel Islands. Her work and the role of dedicated individuals and organizations, such as The Nature Conservancy, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, U.S. Geological Survey, and others, is a story of resilience and recovery and it serves as a beacon of hope for the broader field of conservation.

I wanted to sit down with Heather and learn more about the captivating world of rare plant conservation, a world that often operates behind the scenes but is essential for maintaining our planet’s biodiversity. While some plants, by their very nature, have always been rare, others have faced threats due to habitat loss and climate change. Her interview illuminates the challenges rare plant species face and emphasizes the significance of the Garden’s conservation efforts to preserve the foundation of our ecosystem.

As a senior rare plant conservation scientist, what is your primary role at the Garden? How long have you been working towards this effort?

[Heather] I was hired as the third principal investigator in the department of Conservation and Research about seven and a half years ago. Over that time, I’ve had the privilege of growing and developing the rare plant conservation program into what it is today. I had a great foundation laid by retired Garden staff Dieter Wilken, Ph.D. and support from our Director of Conservation and Research, Denise Knapp, Ph.D.

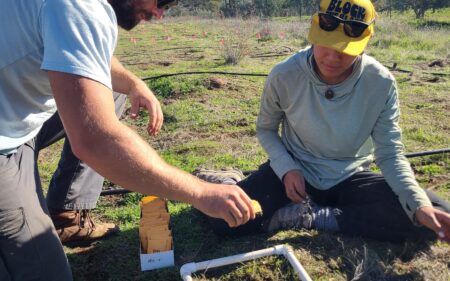

The Rare Plant Conservation Team has a big job – we’re trying to prevent extinction and advance the recovery of California’s rare plants. This means that we spend a lot of time in the field, from the Channel Islands and central coast to central California and the Sierra Nevada Mountains. We’re conducting surveys, monitoring plant life cycles, and collecting seeds for our conservation seed bank. We’re working in the nursery to understand seed germination behavior, reproductive biology, and producing seeds and plants for restoration work. We’re also collaborating with our colleagues at the Garden to answer questions about population genetics and pollinator interactions so that we can approach rare plant conservation in a comprehensive way. Whenever I get the chance, I’m spreading the word about the importance of rare plant conservation with the public to build more support for our work.

What makes a plant rare?

There are many factors that can affect whether a plant is rare. We can break them into two general categories: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic factors include threats like habitat loss due to development and climate change. Intrinsic factors refer to something about the plant that makes it inherently rare. For example, some plants have strict soil preferences which means they can only grow in a specific location. Plants like this were probably always rare, while those affected by extrinsic factors may have been more widespread but have since dwindled over time. Many plants experience a mix of both factors.

Your project contributed to the “proposed delisting” of the Santa Cruz Island Dudleya from the Endangered Species List. Can you tell me a bit more about what this means? How did this plant get on the list in the first place?

Santa Cruz Island Dudleya (Dudleya nesiotica) was listed as rare by the state of California under the California Endangered Species Act in 1979 and as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act in 1997. Like many plants on the Channel Islands, the Dudleya was threatened largely by the impacts of introduced animals, specifically herbivory, erosion, and soil disturbance resulting from the activities of feral pigs. Other concerns include competition with invasive grasses, climate change, and the fact that the plant grows in just one location on Santa Cruz Island.

All feral ungulates were removed from Santa Cruz Island by 2006, allowing plants like Santa Cruz Island Dudleya to recover naturally. Data from previous surveys suggest that the abundance of Dudleya has increased since 2006, likely in response to the removal of the pigs. The proposed delisting means that the threats to Santa Cruz Island have been diminished and that recovery is sufficient to suggest that these plants could be self-sustaining over the long term without additional protections. The goal of the Endangered Species Act is to not just protect rare plants, but also to facilitate their recovery. When a plan does well enough to be proposed for removal from the list, that’s a success story.

What makes these plants so unique? Can you tell me a little about them and why their survival is important?

California is the most biodiverse state in the U.S. and a globally recognized biodiversity hotspot. The Channel Islands represent a major source of biological diversity for California – including a number of plants that occur nowhere else on Earth. Santa Cruz Island Dudleya and island bedstraw are both examples of plants that are endemic to the Channel Islands, meaning that if we don’t save them there then we’ll lose them forever. Both of these plants were impacted by feral animals that were introduced to the islands by people and both have made major strides toward recovery since the animals were removed. Although these plants only occur in a few locations, they can still represent critical linkages in the web of life, supporting pollinators and other animals. I also strongly believe that there is inherent value in all life on this planet. Humans caused these plants to decline and now it’s our job to help them recover.

You’ve said collaboration is key to conservation. Who was instrumental in meeting the criteria needed to propose delisting?

The Nature Conservancy owns and manages the land that Santa Cruz Island Dudleya occupies. They’ve been dedicated to recovering this species for a long time. John Knapp has led that charge for the last decade or so and has facilitated my work on the island. Other collaborators like Kathryn McEachern at the U.S. Geological Survey and Ken Niessen, who is now at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have also played a large role in recovering this plant. The Garden’s own Dieter Wilken, Ph.D. studied Santa Cruz Island Dudleya in the 1990s and helped us understand its reproduction and life cycle.

How long were you working on this project?

I did my first survey for Santa Cruz Island Dudleya in 2017 with John Knapp from The Nature Conservancy, but the one that had the biggest impact was a 2019 survey that the Garden’s Rare Plant Field Program Manager Sean Carson and I conducted with the help of two colleagues. In that case, we used a grid-based mapping system to survey and map plants in a repeatable way. This survey provided the latest estimates of Dudleya abundance and laid the groundwork for future surveys to follow the plants after delisting.

What were some of the biggest obstacles you encountered?

Logistics are always a major challenge on the islands and this work was no exception. In the case of island bedstraw, which has historically been relegated to cliffside habitat, helicopter surveys are the most efficient way to assess populations. However, it’s not always easy to get permission to fly a helicopter over the islands. There were a lot of hurdles to conducting those surveys, but our partners at Wildland Conservation Science finally got it done and provided high-accuracy data and imagery that helped build the case for island bedstraw recovery.

One of the challenges with Dudleya is that it’s not visible aboveground all year and some plants won’t emerge aboveground in drought years. We had to time our surveys right to get the most accurate counts possible and avoid greatly underestimating the number of plants on the island.

What lessons can you or our readers take away from this work to improve their own gardens or open spaces?

Although it might be hard to imagine how rare plant recovery on remote islands can inform backyard gardens, I think the most important lesson is that all plants have a role to play in the web of life. The more pieces that we can keep in our ecological networks, the healthier the planet is as a whole

When you plant natives in your garden or volunteer to help restore a local open space, you’re helping to restore the web of life and that will have trickle-down effects on the native habitats all around you.

Now that these are headed towards recovery, is the work done? What’s next?

Getting these plants off of the endangered species list is a huge win for conservation, but our work is not done. Although the trajectory is positive, we need to ensure that things don’t get off track once we remove protections. To that end, post-delisting monitoring plans will be developed and executed for both species. The Santa Cruz Island Dudleya post-delisting monitoring plan is modeled after the work that my team conducted in 2019 and we’re ready to support our partners at The Nature Conservancy by conducting those surveys over subsequent years in the future when the time comes.

Conservation work requires a lot of patience, what keeps you motivated?

My job gets me outside to beautiful places and in the presence of incredible plants regularly for at least half of the year. Being outside in nature, knowing that I’m doing something to help the planet and plants that I love recharges me in a way that nothing else can. Whether I’m strolling through the Garden’s Redwood Section or hopping out of a helicopter on Santa Cruz Island, I’m filled with a sense of awe and gratitude for the natural world. I’m just honored to get to play a role in saving it.

What does a typical day look like for you?

There’s no such thing as a typical day and what I’m doing depends on the time of year. My team and I are out in the field for at least two weeks a month from roughly February through August, with dribs and drabs of fieldwork tailing into October.

When I’m not in the field, I’m analyzing data and writing reports while also pursuing the next grant opportunity to keep our work moving forward. We clean a lot of seeds in the fall and winter, bolstering our Conservation Seed Bank, which acts as an insurance policy against extinction in the wild. Sometimes I get to spend time with people who also care about plant conservation at conferences, public lectures, and outreach events. My job has a ton of variety, which keeps it interesting and means that I’m always learning something new.

If you could ask our readers to do one thing related to conservation, what would it be?

Don’t be afraid to take action! I’m going to cheat a little bit here by qualifying that the action people choose can be tailored to their own interests and abilities – take a hike, become a member at the Garden, volunteer to pull weeds or restore habitat, plant a native plant, or support legislation that protects open spaces. There’s no wrong way to support conservation, as long as you do something!

Donate

Donate