In the Service of Seeds: A Tale of Two Collectors

Do you ever wonder what the rare plant technicians get up to during the summer? Let your curiosity be quenched in this tale of two collectors. But first, a little background.

The Department of Conservation and Research at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden (the Garden) partners with many organizations and agencies to accomplish our conservation projects. In 2022, the Rare Plant Conservation Team at the Garden partnered with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to collect seeds for the Seeds of Success program.

What is SOS?

Seeds of Success (SOS) is a national seed collection program that was established in 2001 and is led by the BLM. In partnership with organizations in the public and private sectors, SOS partners collect seeds of common native plant species for ecosystem restoration and conservation research. The mission is to increase the quality and quantity of native plant materials for restoring and supporting healthy, resilient, and adaptive ecosystems. To achieve this goal, collections must contain genetically diverse seeds from multiple populations across a species’ geographic range. This means making at least 10-20 collections per species, across the area in which it occurs. It may take several years of collecting to ensure that collections contain genetically diverse and adaptable seeds. For this reason, all SOS teams are trained to collect using the same protocol and coordinate species targeting with local offices.

Where does the Garden come in?

Two technicians on the Rare Plant Conservation Team, Matt Wang and I, were trained under this SOS protocol for the 2022 field season. As two technicians new to California, we didn’t know what to expect in the way of local flora but we were dreaming of hills covered in wildflowers. It turns out we didn’t need to dream for long, because that’s exactly what we got! Within a few weeks of being at the Garden, we took our first trip to San Joaquin River Gorge in Fresno County (BLM Bakersfield Field Office). The area was teeming with early spring energy. Pollinators were out in full force and the hillsides were a patchwork of shrubby greens, fiddleneck (Amsinckia) yellows, lupine (Lupinus) purples, and California lilac (Ceanothus) whites. We couldn’t wait to explore and find promising populations to scout for SOS. Our targets were native plants ranging from herbaceous annuals to perennial shrubs that would be appropriate for restoration in response to disturbances such as overgrazing, recreation, or climate change-driven weather events. Per SOS protocols, each scouted population must contain more than 50-100 individuals and produce sufficient seed to allow us to collect 20% of it without impeding reproductive success.

A typical trip involved setting up camp each night in a new place. This meant never knowing which early-morning bird alarms would wake us up before the sun was barely peeking over the hills. We started our day at 7 a.m. and immediately headed for the hills. We walked trails and slowly drove up a network of roads until our eyes locked on large patches of color. If something looked promising (well over 50 plants in a population), it was time to BOTANIZE! Armed with hand lenses and rulers, we got to know the unique characteristics of our target plants and took the time to work through the Jepson Manual (California’s most comprehensive flora). Identifying plants this way quickly became a regular and rewarding part of our field work. In those moments of identification, while sometimes frustrating, the world slows down just enough for you to greet this unfamiliar plant by its scientific name. If that plant was a common native with a large population, we would conduct a survey and map the site using GPS to revisit later in the season when seeds were ready for collection.

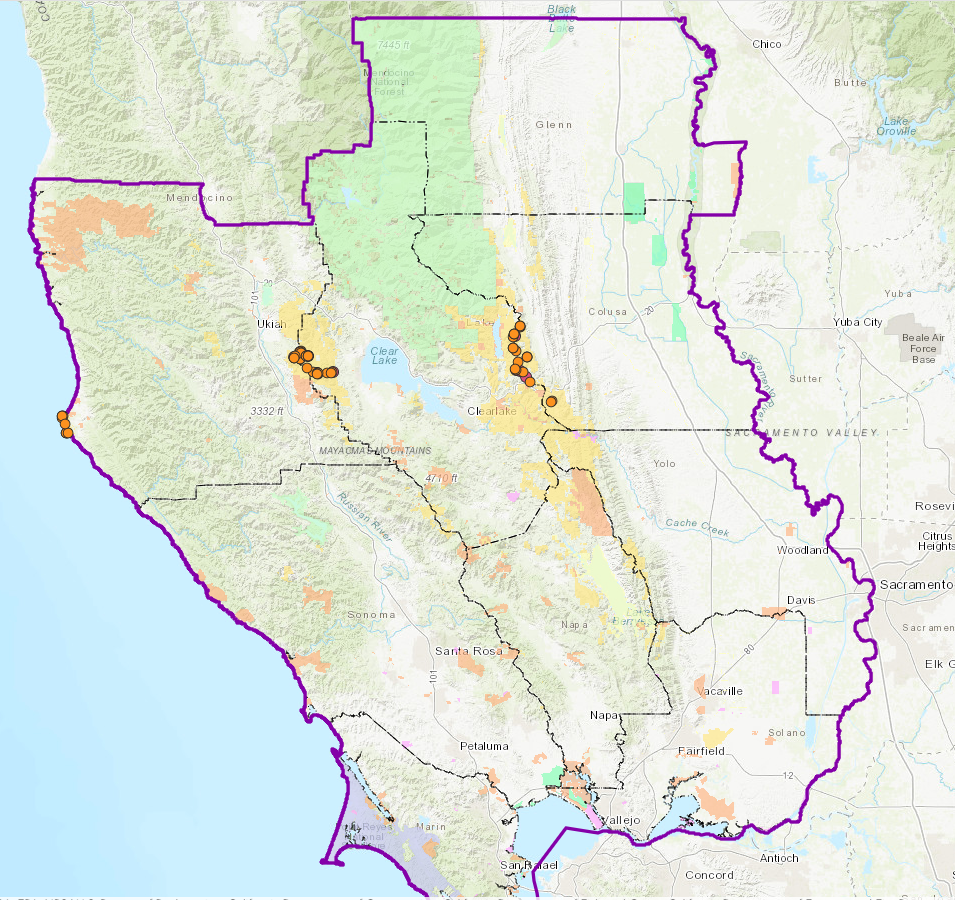

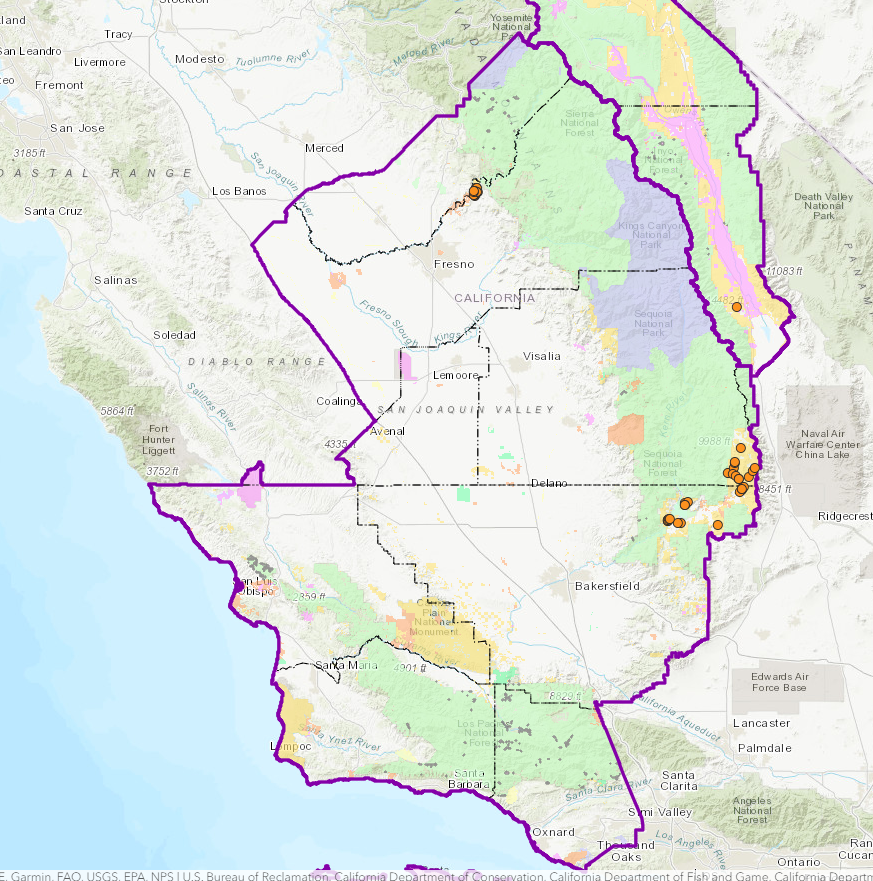

As the field season picked up steam, we bounced back and forth between the BLM’s Bakersfield and Ukiah field offices. Within each office region, we worked across three different geographical areas (Figure 1). As we visited these different ecoregions, we wandered ridgelines, crossed meadows, and meandered along ocean bluffs. Each area holding a diverse range of plant communities and unique taxa.

BLM land is denoted in yellow. Areas visited in the Ukiah Field Office (from west to east) include California Coastal National Monument in Point Arena, South Cow Mountain Recreation Area, and Indian Valley. Each area is represented by a cluster of orange dots which indicate scouted plant populations.

Areas visited in the Bakersfield Field Office included San Joaquin River Gorge Special Recreation Area and the Lake Isabella Region. On the map, BLM land is shaded in yellow. Orange points on the map indicate populations where data, specimens and seeds were collected.

Figure 1.

Every few weeks, we returned to each field site to scout new populations of flowering plants or to collect seeds from the populations that we scouted previously. If seeds were ripe, then it was time to collect! But first, we had to ensure that a population met the requirements for an SOS collection. First, we inspected seed viability by performing a cut test in the field. To do this, Matt or I used a knife or razor blade to cut a seed in half and examine it with a hand lens. If seeds looked healthy and filled, then we could move to the next step. Second, we estimated seed production to ensure that 80,000 seeds could be collected without taking more than 20% of the available seed. Collecting 20% or less of the available seed helps to ensure that we’re not doing harm by over-collecting. If these requirements were met, then a collection was made.

In addition to collecting conservatively, it is also important to get an accurate representation of the genetic diversity across a population and species’ range to avoid future maladaptation or genetic bottlenecks in restored populations. To capture as much genetic diversity as possible, we collected from more than 100 individuals evenly and randomly across the population’s distribution. Every collection made was one step closer to our goal, but more rewardingly we had the opportunity to observe a plant population through its full reproductive life cycle. Not only did we get to identify plants in their flowering stage, but we became more familiar with what their seeds look like and how many they will produce on average. Watching plants move through the entire life cycle is something everyone can experience to get to know the local flora. It’s easiest to focus on annual wildflowers, which complete their life cycle in a single year. If there is a native plant you are particularly fond of, I would encourage you to explore what that plant looks like throughout its life history stages (e.g., seedling, flowering, fruiting, etc.).

What is the future of these seeds?

By the end of the field season we made 41 collections across both BLM field offices, which gave us an estimated total of 1,912,465 seeds from 33 unique taxa. That means that the Garden contributed nearly two million seeds to future conservation on BLM land in just one year! However, collecting the seeds is only the first step in their journey to restoration. Once back at the Garden, these precious seeds were packaged in individually labeled brown paper bags, packed into a box and hand delivered to the designated BLM field office. From there, they will make their way to a national seed lab in Bend, Oregon to be carefully cleaned and counted. And still, their journey is far from over. After cleaning, the seeds have several possible paths. The first 3,000 seeds from a collection are placed in long-term storage at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation (our country’s national seed bank) in Fort Collins, CO to act as a genetic backup of wild plant populations. Others will be placed in short term storage in Bend for eventual use in partnership with local farmers to increase native seed availability where the seed will be used. Imagine a football field full of native California wildflowers grown out and harvested to increase seed quantity for restoration. The third option for our seeds is allocation to a specific project. According to the SOS technical protocol “Projects using SOS seeds may include emergency fire rehabilitation and restoration, wildlife habitat, pollinator habitat, threatened and endangered species habitat, and roadside revegetation and waterway stabilization…SOS collections focus on areas that may be vulnerable to climate change and extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, floods, drought, and wildfire.”Thus, every viable seed collected has the potential to help promote healthy ecosystems and biodiversity in the face of climate change. When walking through restoration areas in the future, you could be seeing the plants grown from the seeds that we collected!

Beyond collecting seeds, the Rare Plant Conservation Team at the Garden conducts conservation and research across the state and collaborates with multiple local, state and federal partners to safeguard the remarkable diversity of California’s rare plants both in our conservation seed bank and in nature. Whether for SOS or other projects, the seeds our team collects will facilitate future restoration in the regions from which they were collected.

After a long field season, the multitude of collections that the Rare Plant Conservation Team brings back to the Garden need to be cleaned and counted. We rely on volunteers to join us in our effort to make sure these seeds fulfill their conservation destinies. If you would enjoy spending a few hours getting to learn about the seeds we collect and helping in this important part of conservation, please contact Heather Schneider, the Garden’s Rare Plant Biologist.

Hschneider@SBBotanicGarden.org

More information about the SOS program is available on the BLM website at this link:

Donate

Donate