What is a lichen?

If you Google the word “lichen” some of the results will invariably talk about the skin disease “lichen planus”. That is not what this insight is about. Rather it is about a very interesting group of organisms that play important roles in our ecosystems.

A lichen may look like a single organism, but each is actually a complex entity that consist of several organisms living in symbiosis. There’s the main fungus which makes up the structure of the lichen, and it is also the part you see when you look at a lichen growing on a rock, a tree, or the ground. There’s also the green algae or cyanobacteria or sometimes both in the same lichen. They produce food for themselves and the fungus via photosynthesis. On top of that, researchers are finding more and more other organisms that seem to be part of the relationship, although their functions are largely unknown so far. These additional organisms include different kinds of yeast and bacteria. You could therefore say that every single lichen is a little ecosystem in itself.

Three Major Growth Forms

For practical reasons, lichens are often divided into groups depending on their growth form. It is important to know that similar growth forms don’t necessarily mean that the lichens are related. There are three major growth forms:

1. Foliose lichens resemble a leaf with an upper and a lower surface.

2: Fruticose lichens are three-dimensional with no difference between the upper and lower surface. Fruticose lichens often look like a tiny shrub that is either erect or pendant.

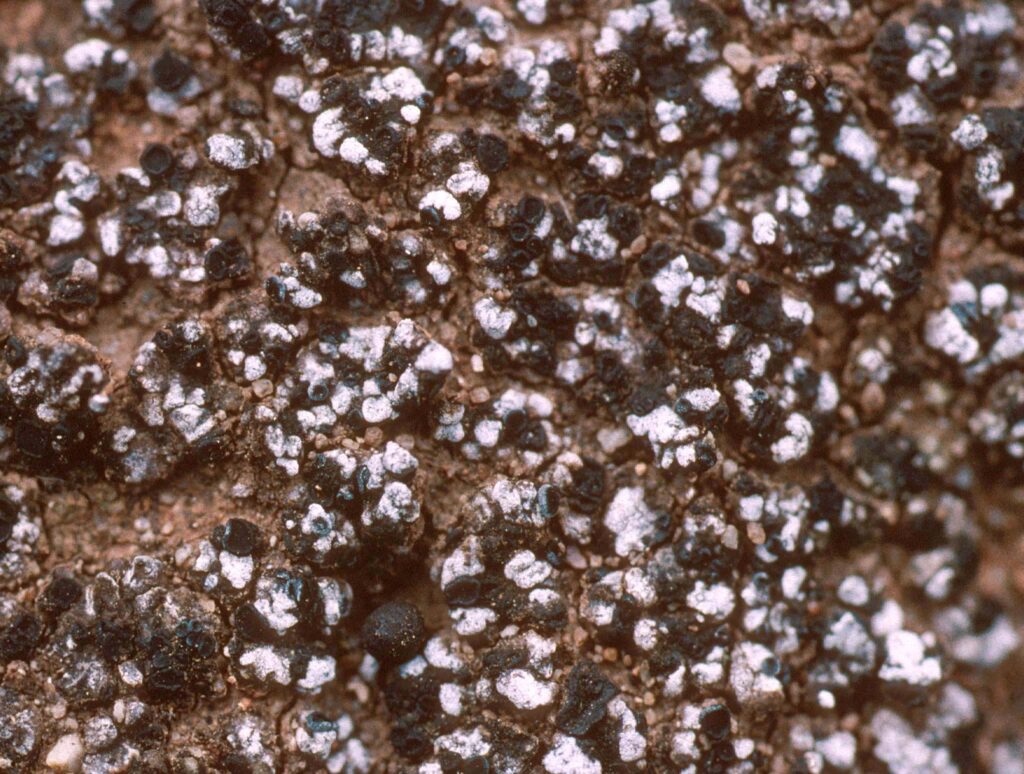

3. Crustose lichens are so firmly attached to the surface they grow on that you would have to take that surface with you in order to collect the lichen.

Chemical Reactions

Many lichens produce chemical compounds; more than 700 different compounds unique to lichens have been identified. Apart from giving lichens their beautiful colors, these compounds perform adaptive functions. Some compounds deter animals from eating the lichen. Others are used as chemical warfare against other lichens and mosses in order to secure a space to grow. Other compounds reduce the intensity of incoming sunlight to protect the algae from damage. Humans even benefit from some lichen compounds that are known to have antibiotic, antiviral, antioxidant, or antifungal properties. Fortunately for lichenologists, these chemical compounds can aid in lichen identification since addition of certain chemicals, e.g. household bleach, produce a color reaction when applied to some lichens, but not to others.

Sexual Reproduction

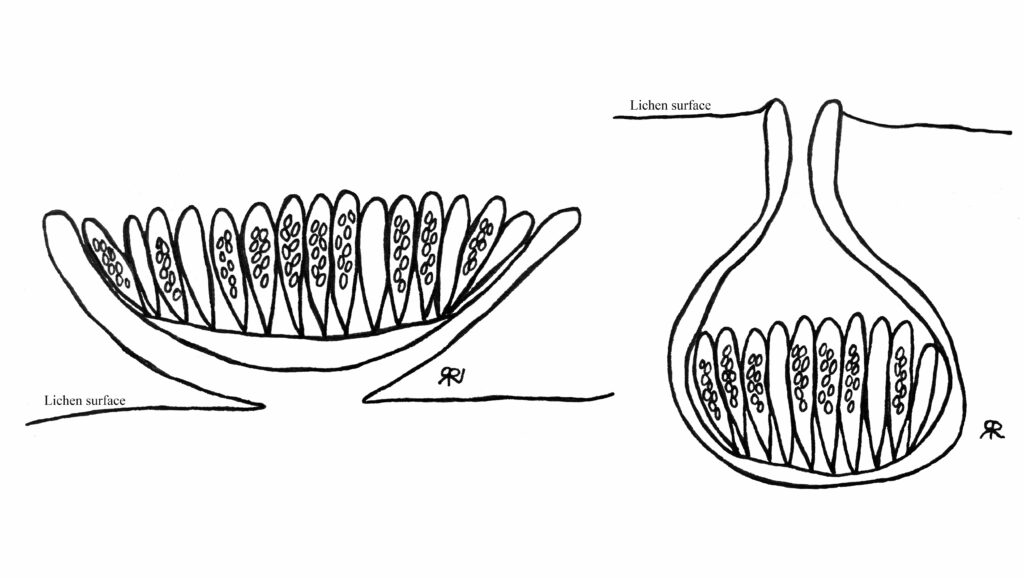

Lichens reproduce sexually with two main types of fruiting bodies: apothecia and perithecia.

Even though they look a little different—one looks like a tiny bowl while the other looks like a flask—their function is similar.

This is the place where the fungal spores are produced. Sexual reproduction in lichens poses a problem most other organisms don’t face. Sexual reproduction generates fungal spores that do not contain the other components of the symbiosis; that is, each spore has to find a new photosynthetic partner (and perhaps other organisms too) in order to grow into a new lichen. This can be achieved by partnering with free-living algae or by stealing algae from a lichen that is already established.

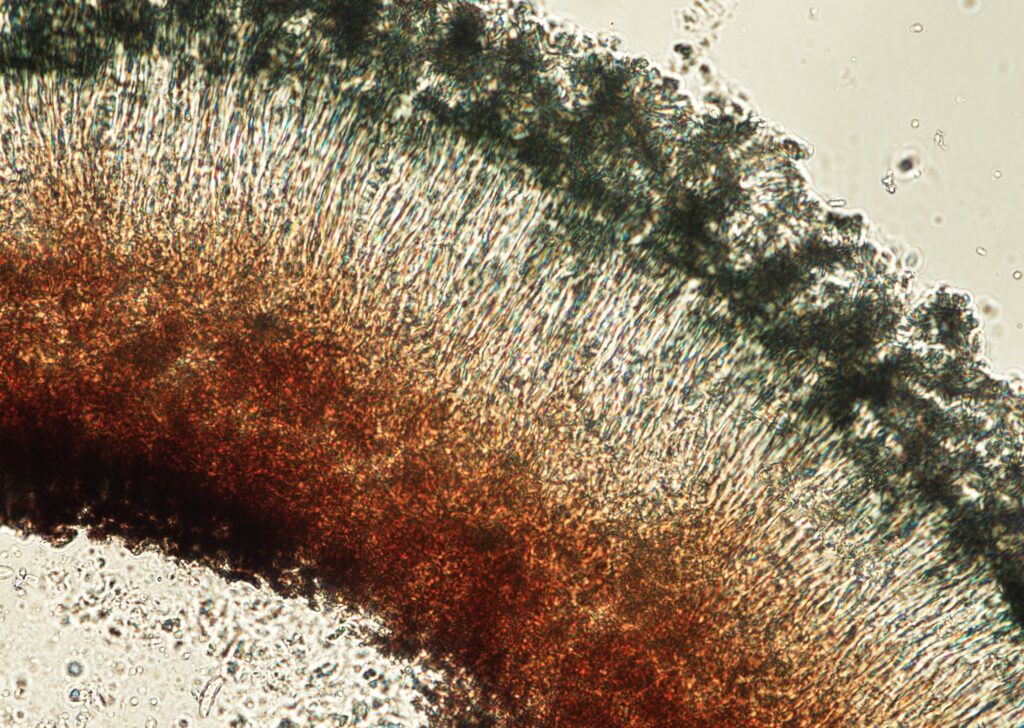

Cross Section of Apothecium

This is a cross section of the apothecium of a lichen called aromatic Toniniopsis (Toniniopsis aromatica), which is a rather inconspicuous greyish crustose lichen with black apothecia. It grows on soil. Each apothecium is only around 0.04 inches, and cutting a thin section through one reveals its private parts. The red-brown color at the bottom is the foundation for the sacks where the fungal spores are produced. The spores are produced inside the little sacks that are visible in the pale part in the middle, and the greenish part is the top of the apothecium exposed to the air. If you look carefully in the lower part of the photo there’s a sausage-shaped spore—this spore is only around 0.0006 inches long. That’s four to five times smaller than the diameter of a human hair, and more than twice as small as anything you’d be able to see with the naked eye! These are the kinds of details lichenologists routinely pursue in order to distinguish between different species of lichens.

Asexual Reproduction

Many lichens have developed other ways to reproduce. Some lichens reproduce asexually via areas of powder-like propagules of algae or cyanobacteria surrounded by fungal hyphae. These areas are called soralia and the powder-like propagules are called soredia. Soredia rub off very easily and since they contain both fungus and the photosynthetic partner, they can grow into new lichens without having to find a new partner to form the symbiosis

Using a variation on this theme, some lichens produce tiny finger-like protrusions from their surface. These are called isidia. Like soredia, isidia also contain both the fungal and photosynthetic partners and can also grow into a new lichen without having to find a new partner.

Finally, many lichens can reproduce just by simple fragmentation, that is, the body of the lichen breaks into two or more pieces and each piece continues to grow. Fragmentation is the most common way for old-man’s beard (Dolichousnea longissima) to reproduce.

What are lichens good for?

Lichens provide many important ecosystem services. Lichens contribute to biodiversity—there are at least 18,000 species of lichens in the world and they are found in all biomes, including ecosystems ranging from some of the driest deserts to Antarctica.

Some lichens are pioneers, so they are often the first to occupy newly exposed surfaces. Chemical compounds released from pioneer lichens slowly break down newly formed volcanic rock in a process that initiates soil formation and facilitates establishment of other species, such as plants. Lichens also contribute to nutrient cycling—in some old-growth forests lichens contribute up to 50% of the nitrogen. Many animals use lichens. Up to 90% of reindeer’s winter food consist of lichens, and other animals use lichens for nesting material, hiding places, and camouflage.

Lichens can also inform us about the condition of our environment. Many lichens require very specific environmental conditions and cannot tolerate large fluctuations from their optimum. For example, presence of certain lichens can be an indicator ecological continuity leading to old-growth conditions. Others are sensitive to large fluctuations in temperature and they can help us track climate change. Some lichens are sensitive to air pollution and will disappear when air quality is poor.

Look for lichens at the Garden!

Want to learn more about lichens? Take a close look at the growth forms, substrates, and fruiting bodies of the lichens in your environment. If you’re at the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, try looking for these familiar lichens. Please remember to observe lichens without going off trail or trampling plants.

Green rock shield lichens (Xanthoparmelia spp.)

Growth form: foliose

Substrate: rock

Fruiting bodies: brown apothecia or soredia (apothecia and soredia are not always present)

Where it can be found at the Garden – Blaksley Boulder

Golden hair and Golden eye lichens (Teloschistes spp.)

Growth form: fruticose

Substrate: bark

Fruiting bodies: bright orange apothecia that in one species have “eyelashes” at the edges (apothecia are not always present)

Where it can be found at the Garden: on trees in the Desert Section

Lichen identification frequently relies on descriptions of growth forms, substrates, and fruiting bodies. If you’ve found a lichen that you’re interested in identifying, try looking at these characteristics and matching them to species descriptions in guide books. Taking notes and close up photos of lichens can be a helpful aid in identification and remembering what you saw when you are no longer in the field. Photos and information about local lichen species can be found in resources such as A Field Guide to California Lichens by Stephen Sharnoff and Lichens of Sedgwick Reserve and Santa Barbara County by Shirley Tucker. A Field Guide to California Lichens can be found at the Garden’s gift shop and Lichens of Sedgwick Reserve and Santa Barbara County is available for free online

Donate

Donate