Son muchos líquenes

El departamento de Conservación e Investigación del Jardín trabaja para documentar la biodiversidad de California y parte de ese trabajo se realiza en su liquenario.

Gran parte de los esfuerzos de conservación e investigación del Jardín implican que el personal salga al campo para observar los seres vivos en sus hábitats naturales. Sin embargo, hay otra faceta del trabajo que se queda en el Jardín. En el sótano del Centro de Conservación Pritzlaff hay un museo que contiene miles de colecciones de plantas y líquenes de todos los continentes. Estas colecciones proporcionan información importante sobre dónde y cuándo han existido los organismos en el paisaje y, por tanto, pueden informar sobre muchos aspectos diferentes de la investigación, como la ecología de las comunidades, los cambios en el uso del suelo y los efectos del cambio climático. El museo se compone de un herbario, que alberga especímenes de plantas, así como de un liquenario, que alberga colecciones de líquenes. El liquenario contiene 35.500 líquenes, cada uno de ellos cuidadosamente encerrado en un paquete o caja. Pero esa cifra está a punto de cambiar porque el liquenario ha recibido recientemente una donación de 16.000 líquenes de la Universidad de California Riverside.

El Jardín recibió una donación de líquenes de la Universidad de California Riverside, lo que convierte al liquenario del Jardín en la mayor colección de líquenes de California.

El equipo del liquenario ha ido incorporando estos nuevos líquenes a la colección actual. Eso significa que cada espécimen, incluidos los "viejos especímenes" de la colección del SBBG, se manipula manualmente para añadir un código de barras, asegurarse de que los nombres científicos están actualizados y verificar que la información descriptiva de los envases se introduce correctamente en la base de datos en línea. Se espera que este trabajo dure al menos un año entero. Una vez finalizado, los datos de cada ejemplar de liquen de la colección estarán a disposición del público en el Consortium of North American Lichen Herbaria(CNALH). En ese momento, el liquenario contendrá unas 51.000 colecciones individuales de líquenes, lo que lo convertirá en el segundo liquenario más grande de California.

¿Qué se necesita para recoger especímenes de líquenes?

A diferencia de las plantas, la mayoría de los líquenes crecen tan pegados a su superficie que no pueden separarse unos de otros. Para recoger estos especímenes, los investigadores tienen que retirar el liquen junto con lo que está creciendo. En el caso de los líquenes que viven en la corteza, los investigadores utilizan un cuchillo para retirar la fina capa exterior de la corteza que sostiene al liquen. En el caso de los líquenes que viven en la roca, los investigadores utilizan un cincel y/o un martillo para romper las secciones de roca en las que crecen los líquenes. Una vez recogido el liquen, se transfiere a una caja o sobre junto con la información sobre el lugar donde se recogió. El espécimen se almacena en un liquenario, donde sirve de registro de la presencia de un liquen en un lugar y un momento determinados.

Más de un tercio de todas las especies de líquenes de Estados Unidos se encuentran en California.

A pesar de la enorme cantidad de colecciones, el liquenario del Jardín no cuenta actualmente con un ejemplar representativo de todos los líquenes que se pueden encontrar en California. Hay más de 2.000 especies de líquenes en los diversos paisajes de California, lo que supone el 36% de todos los líquenes que se encuentran en Estados Unidos. Por ello, es importante que los liquenólogos sigan recogiendo, identificando y depositando colecciones de líquenes en los liquenarios. Con registros continuos de líquenes, los investigadores pueden analizar cómo ha cambiado la biota de los líquenes a lo largo del tiempo y del espacio y, por tanto, comprender mejor cómo responden los líquenes vivos a los cambios del medio ambiente.

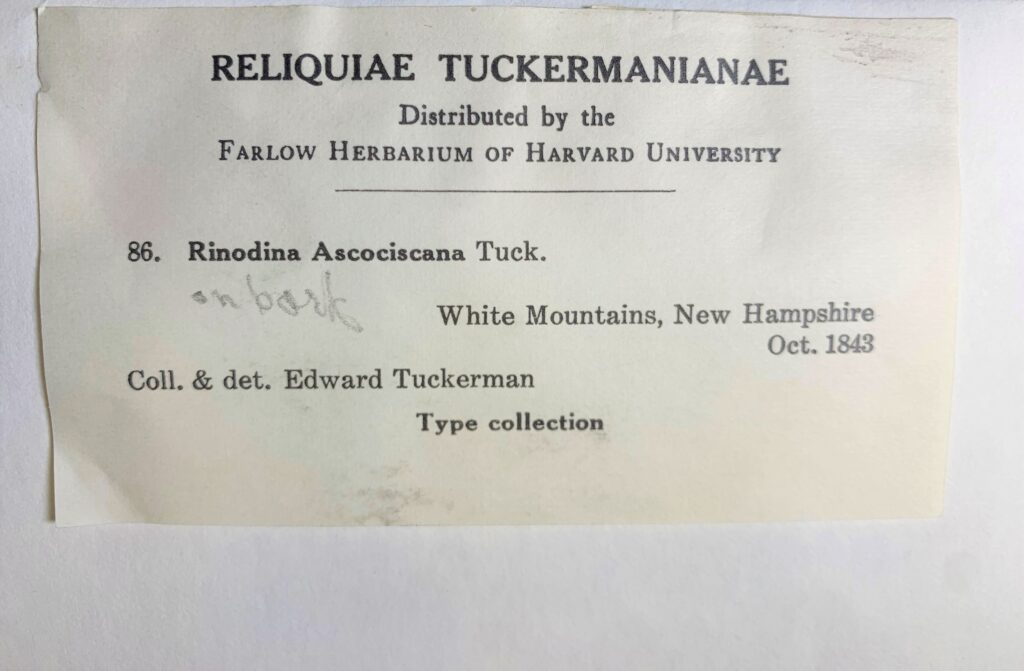

El liquenario contiene el ejemplar de museo más antiguo de las colecciones del Jardín.

Por ejemplo, el liquenario alberga un liquen recogido en 1843 en New Hampshire por Edward Tuckerman, que dio forma a la liquenología norteamericana. Este liquen es el espécimen más antiguo recogido en el Jardín. Aunque no se menciona la localidad exacta de recogida en esta colección, al menos sabemos que el liquen Rinodina (Rinodina ascociscana) se dio en las Montañas Blancas de New Hampshire hace casi 200 años.

Donar

Donar